Professions

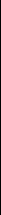

African Americans like Ezra Gerry contributed to Pensacola's growing economy at the turn of the twentieth century. Although Jim Crow laws began to trickle into Pensacola, the city’s African-American business community continued to thrive, and many African-Americans managed to demonstrate their professional successes in a number of fields. Working-class African Americans like Gerry acted as a strong foundation for the city, making up a large portion of port workers in a city so dependent on its port. African-Americans made up 43% of Pensacola’s workforce during this time; of these “professionals and merchants made up 2%, services and skilled labor 6%, and unskilled and shipyard laborers 35%.”

Educated Professionals

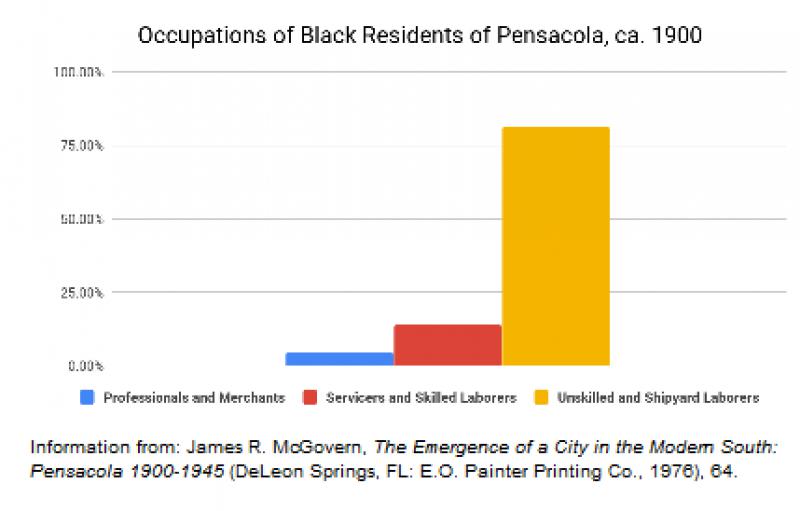

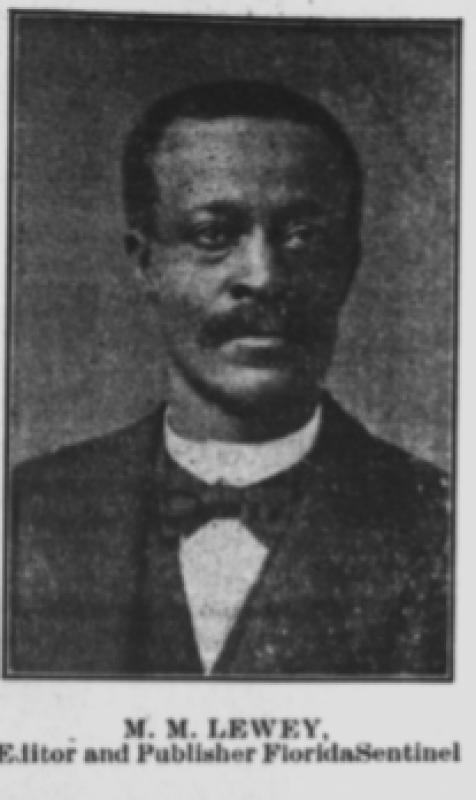

A number of Pensacola’s African-American citizens became respected professionals and businessmen. Four African-American physicians served the area in 1904. Two Pensacola attorneys and a veterinarian also counted themselves among the African-American professional class at this time. From 1894 to 1914, Pensacola served as the home of Matthew Lewey and headquarters for his newspaper the Florida Sentinel, a publication devoted to reporting on news of interest to Florida’s African-American communities. He became highly involved in the National Negro Business League, an organization established by Booker T. Washington in 1900 to promote the interests of African-American business leaders.

Businessmen

Some of Pensacola’s African-American professionals also had experienced success as business owners. In addition to being a physician, Dr. Henry G. Williams also owned and operated a pharmacy on the southern portion of Palafox St., the city’s main business district. Reportedly, Pensacolians both black and white frequented Dr. Williams’ drug store. In 1900, when Ezra was about twenty years old, Dr. Booker T. Washington, founder of the National Negro Business League and renowned speaker and educator, came to Pensacola at the invitation of the Afro-American Business and Professional Men’s Association. This visit excited the people of Pensacola, black and white. Based on this visit, Washington characterized Pensacola as having a thriving African-American business community. He presented Pensacola as a model city of African-American businesses and professionals, saying that it demonstrated “that healthy, progressive, communal spirit, so necessary to our people.”

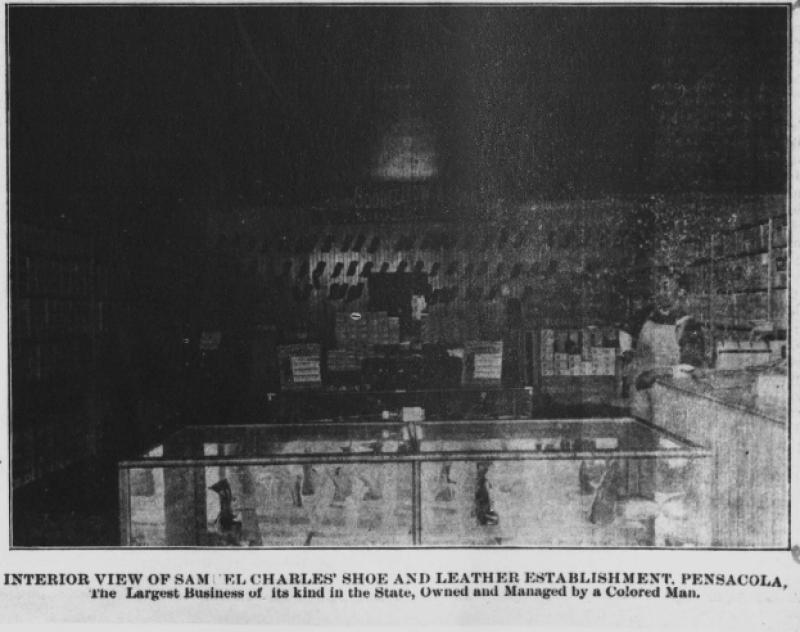

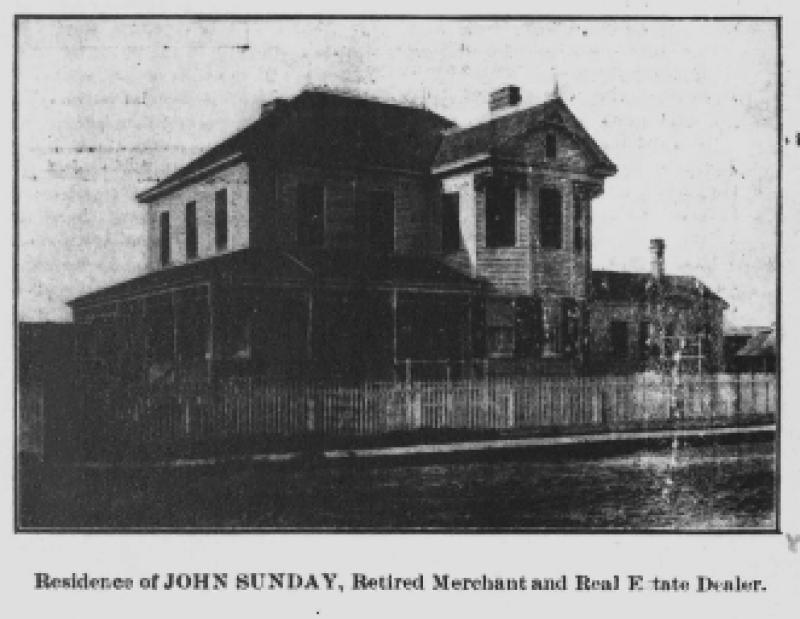

At the end of the nineteenth century, the southern portion of Palafox St. boasted racial diversity, hosting businesses owned by both black and white proprietors. Two pharmacies, along with Samuel Charles’s shoe and leather shop, were among some of the Palafox businesses owned by African Americans. Additional African-American businesses were also located a street or two away from the main business district. Daniel J. Cunningham operated one such business. His grocery store attracted both black and white customers. West of Palafox St., John Sunday Jr. acted as another influential pillar of the business community. Born to an enslaved woman around 1838, John Sunday Jr. went on to find work as a contractor in Pensacola. People in the community respected Sunday as a successful merchant and real estate dealer.

Laborers

In addition to serving the community as professionals and successful businessmen, African Americans like Ezra Gerry served the Pensacola community as skilled craftsmen, domestic workers, and laborers. The large proportion of laborers reflects the influx of rural black Southerners around this time, like Gerry and his family, who moved to Pensacola from Milton. These individuals came to Pensacola seeking job opportunities they could not find in their rural communities. For them, the bustling port city represented a chance to move to a more urban environment while easily transferring their experiences of physical, often agricultural, labor. Many labor organizations, such as the Cotton Screwmen and the Baymen’s Protective No. 2 Association, defended the rights and interests of working class African Americans in the city.

Further Reading:

Florida Department of Health and Vital Statistics. “Death Certificate of John Sunday Jr.” in Florida Deaths, 1877-1939, Death certificate, Jacksonville, from Familysearch.com.

Jackson, David H., Jr. “Booker T. Washington’s Tour of the Sunshine State, March 1912.” Florida Historical Quarterly 81, no. 3 (2003): 254-78.

Lewey, Matthew. “Annual Issue.” Florida Sentinel (Pensacola, FL), 1904.

McGovern, James R. The Emergence of a City in the Modern South: Pensacola 1900-1945. DeLeon Springs, FL: E.O. Painter Printing Co., 1976.

Young, Darius J. “Florida’s Pioneer African American Attorneys during the Post-Civil War Era” Master’s Thesis, Florida A&M University, 2005.