Maritime Pensacola

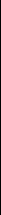

Trade brought in revenue, but it also brought in disease. Pensacola was not immune to national epidemics like cholera and yellow fever. Often ships and even the port itself quarantined to avoid the spread of disease. Quarantine notices, often issued by the Florida Board of Health, regulated the port and dock during epidemics. Workers in the maritime industry regularly encountered a hold in work due to disease and often were exposed to disease themselves.

Those seeking work in the maritime industry could expect a consistent amount of opportunities. Maritime employees had the option to jump from port to port in search of work until they signed onto a ship or company long term. Many maritime employees began their career as “volunteers” after a night of drinking. This practice was common amongst fishing captains, merchant ships, and other labor-intensive fields. However, once working many choose to stay with the line of work for a decent time. Despite fishing captains hiring drunkards for crewmen, many stayed on and the fishing industry in Pensacola employed over 500 men.

Through the Port of Pensacola, workmen and women could connect to different jobs in the maritime industry. Other than longshoremen and stevedores, vessels needed waiters, porters, laborers, janitors, tradesmen, cooks, etc. However, many of these jobs served the gulf coast rather than Pensacola alone.

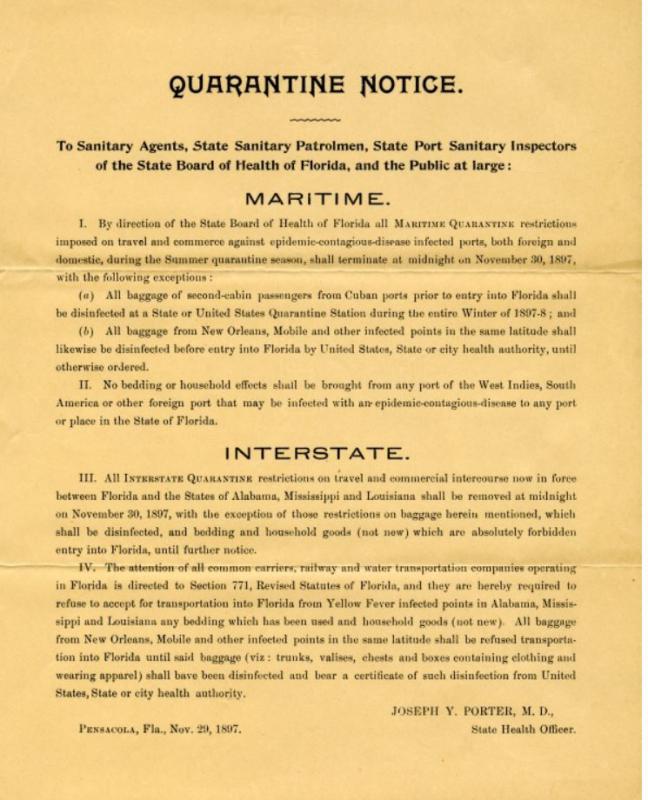

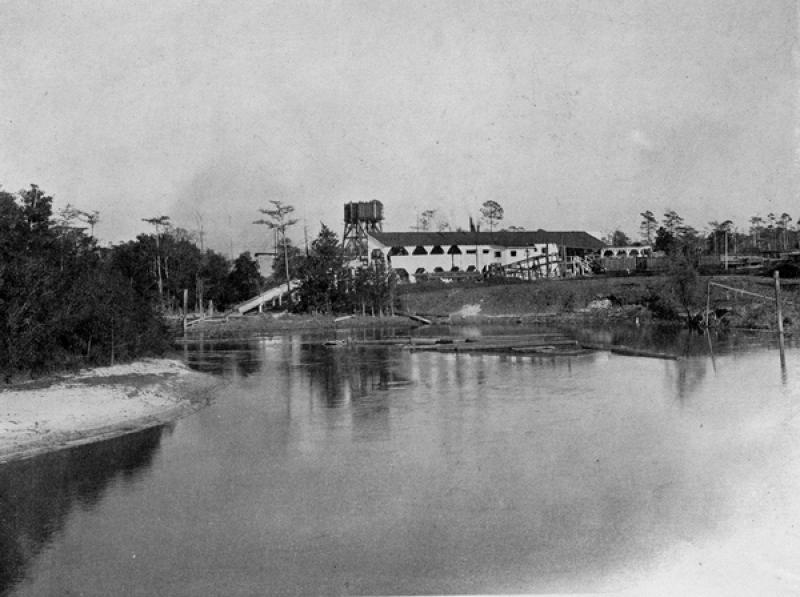

Following the Civil War, the disrupted trade through Southern ports began to flourish again. Pensacola participated in this growing trade. Between 1865 and 1871 Pensacola doubles, and half of this boom is from African Americans flooding in from neighboring rural areas. Many participated in the timber industry. At this time, transportation by the water was cheaper than over land. Timber was bundled together and moved down river to the bay where it was loaded onto ships. This is known as ship brokerage. Pensacola became known as the Yellow Pine Capital of the World. All of this pine crossed the country and globe starting in Pensacola’s Port.

The port would expand further with the reconstruction of Southern railroads. Many of the region’s politicians favored Pensacola’s port to ferry cotton and coal from Alabama’s interior. The Pensacola and Louisville Company rebuilds previously destroyed rail lines. Other railways like the Florida and Alabama Railway Company followed and flourished in the area. Rail lines expanded down Palafox Street and Connect to the navy yard. This pulled migrants to the Port of Pensacola from throughout the Panhandle.

Though many African Americans chose to remain in the sawmills, timber needed to be river rated and to transported to the port. Stevedores were employed to load the timber from wavers. Loading lumber and other heavy goods were typical work for stevedores. Many were poor whites and African Americans looking for work on the busy port. Trade was the largest part of the Maritime industry. Trade over the water was typically cheaper than land until the late 1800s. The lumber and turpentine trade fueled Pensacola’s maritime economy. From to the incoming maritime commerce, other trades benefited from the proximity to the port. Craftsmen, blacksmiths, cigar makers, and other trades that African Americans participated in benefited from the port. Due to the volume of businesses, unskilled laborers easily found work. Many African American men began their maritime careers as laborers loading cargo because that was where they would be hired. Many ships kept laborers aboard as they changed location, so they had a ready supply of muscle when they docked and unloaded.

Once a part of the maritime industry, workers became acquainted with the business. Once a member of the industry, workers had further insight into job offerings. Workers like Ezra Gerry would benefit from continuous knowledge of new opportunities, different employers, and talks amongst fellow workers. Though the locations of ships and their cargo were well documented in newspapers, job offerings were not. Many job openings were communicated through word of mouth.

The Port of Pensacola experienced growing prominence from the maritime industry until 1913. 1913 was the peak year for yellow pine industry. Following that year, the port began a steady decrease in commercial traffic. Trade continued in the greater region- New Orleans primarily, and the fishing industry remained active despite fish depopulations. Despite this lull, the port commerce survived until the enactment of the Naval Appropriation Act. Pensacola’s Navy Yard was converted to a federal navy base and began heavy use following the United States entrance into World War I. This increased trade and shifted commerce in a different direction.

For further reading:

- McGovern, James R. Emergence of A City In The Modern South: Pensacola 1900-1945. The University of West Florida Foundation, 1976.

- Dunlap, Deborah J. and Martin, Tracey L. Historic Photographs Pensacola Vol. 2. Bayshore Publishing Group, 2002.

- Bowden, Jesse Earle, et al., eds. Pensacola Florida’s First Place City. Norfolk: The Donning Company, 1989.

- Porter, Joseph Y. “Quarantine Notice.” The Florida Board of Health. November 29, 1889.

- Williams, George. "Stevedore Protest" Pensacola News Journal. August 13, 1889.

- People Aboard Lumber Ship: Pensacola, Florida. 1910. Photograph. Pensacola, Florida.

- Gulf, Florida and Alabama Railway Company Sawmill no. 4 in Muscogee, Florida. 1903. Photograph. Muscogee, Florida.

- Sawmill at Muscogee. 1903. Photograph. Muscogee, Florida.