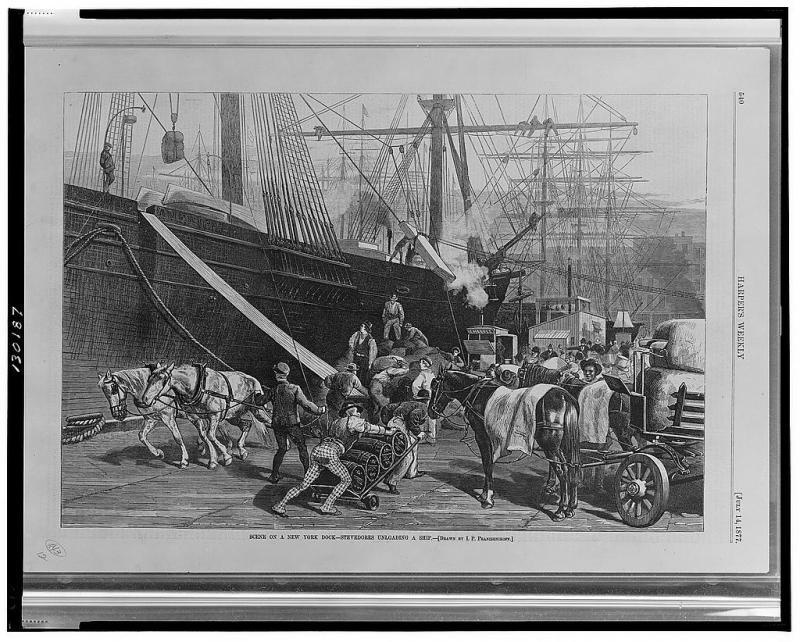

Stevedores and Longshoremen

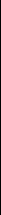

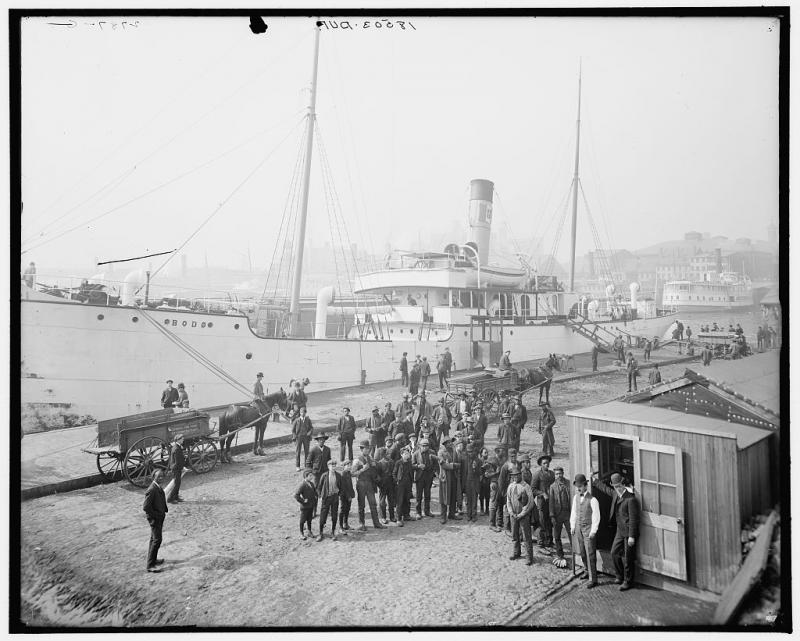

On a sunny day in Pensacola in 1900, a ship pulled into the port. A crew of African American men sitting on the port stood up and made their way over to the ship as it docked. They climbed aboard and began carrying the massive load of cargo off. One of the men told the others he thought it would take the men thirty-hours to completely unload the ship. They all groaned, yet steadily continued their lifting and moving. The sun and weight of the items tired them, yet they persevered. After all the cargo was off, the men began to set about loading lumber onto the ship. Piece by piece, board by board, the ship was carefully filled to not upset the ship's equilibrium. After about thirty hours, as predicted, the job was complete. The men, exhausted, went home to rest. They knew they needed it. Another ship might arrive tomorrow, or it could be as long as a week until another ship arrived. Either way, they knew they needed to rest for the next ship.

What are longshoremen, stevedores, and stewards?

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the longshoreman occupation was a common job for men living in prosperous port cities, such as Pensacola. Among the longshoremen was Ezra Gerry who had found that position at the port. The longshoreman would get together with other longshoremen to form a gang that he would complete their work with. These gangs would wait at the port for any ships to arrive. Once a ship arrived, Gerry and the rest of the gang’s physically demanding job began. The ship would be full of cargo ready to unload and load hundreds of pounds of cargo. The longshoremen worked non-stop loading and unloading cargo sometimes, while other times the work would be short. While longshoremen were performing this back-breaking work, there would be a foreman in place to keep track of the work hours that the longshoreman worked for payment purposes. It was not a dead-end job, however, a longshoreman who has proven themselves at the position could promote up the ranks. Ezra started out working as a pier longshoreman, who transported items taken off the boat to the location it needed to arrive at. He could promote to either deck or hold longshoremen, who deal with cargo placement and moving cargo within the hold respectively. Eventually, he had the opportunity to promote to a stevedore.

A stevedore acts as an agent between shipping companies and the port. If Gerry promoted to the role of a stevedore, he would contract longshoremen gangs to work for him. When a ship arrived at the Pensacola port, Gerry called for the gang to do the heavy lifting.

How was the job different for African Americans?

The employers likely did not treat Ezra Gerry and the other longshoremen much differently than their white counterparts. In Pensacola, there was a very large African American population. with many of the men pursuing careers as longshoremen The public’s perception of longshoremen was not high. Because of the intermittent nature of their work, longshoremen gangs would wait around on the port for a ship to arrive. They could be waiting for hours, or even days. The public saw that they were not working and that perception of the longshoremen when they had no work led them to be characterized as lazy. As African Americans, this thinking might have even more common because of the growing racial tensions in this time.

Yet, stevedores and longshoremen likely did not like their jobs. Though, because they were not allowed to have many other types of jobs, they learned to deal with the hardships in their occupations. There are songs that have been written about how much stevedores do not like their jobs and how they would rather do something else. They may have even sung these songs while they were working!

However, African Americans did have to deal with employers and shipping companies trying to take their jobs and give them to white workers. Even though African Americans were not completely discriminated against in the longshoreman industry, racist whites would still prefer not to have African Americans work a paying job. In one instance in Pensacola during 1873 and 1874, dock owners tried to take African American longshoremen’s occupations and given them to newly arrived Canadians. The African Americans were able to unionize and defend their jobs from their aggressors. Stevedores and longshoremen were some of the first occupations to unionize. They were very strong unions that were good at fighting for what they wanted.

One benefit African Americans obtained from doing such intense work with each other was the formation of a very strong bond. Ezra Gerry and his fellow longshoremen gained a strong sense of unity and togetherness while loading and unloading lumber on the Pensacola Port.

"Yaas, Lo'd, I wan' t' be

A gatekeepah fo' Dee

To turn de key

Quietly

An' pleasantly

Right presently.

I don't wan' t' be a roustabout,

No moah a stevedoah,

I ain't gwine push dem steamboat trucks

When I get t' de golden shoah.

I wan' t' go - far away

Way - way - way -

From whar de steamboat smudge.

Yaas, I'm gwine far

In Dy golden car

Ha! ha!

You're gwine stay right heah an' drudge.

Yaas, you're gwine t' be a roustabout,

A shovin' stevedoah;

To turn Petah's key?

Boy, you'd turn-an' we

Would have t' be

De ste - vedoahs fo' evah"

Why Did Gerry Choose this Line of Work?

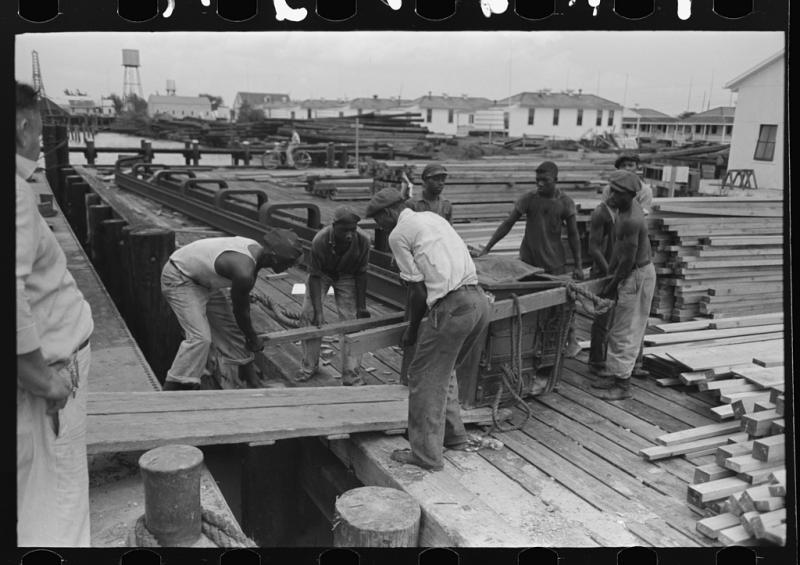

The Maritime industry has been a long-standing employer of African American men. Men with the skill or determination would be hired no matter the color of their skin. Working on the docks or on a ship was long and hard work. Requiring the loading of large quantities of weight for sometimes up to 30 hours. When the ships came to port so did the stevedores/longshoremen. The work was not for the faint of heart or the weak. Ezra Gerry did not go to the port with the idea of becoming rich, but with the goal to support his family and himself.

Ezra did not pick this line of work for the ease of the job or the large paycheck. Nor did he choose it for the fun and excitement some choose jobs today for. Proximity and connections brought him to the port of Pensacola. Being no more than a 20 to 30-minute walk from his home on West Zaragossa. Making the docks an easy place to find work while remaining close to home. With transportation being limited having a job within walking distance became a huge consideration in picking a job.

In the south family plays a large role in the lives of most people. Ezra lived with his family throughout most of his life in Pensacola. One of those being his brother Charlie. Charlie held the same job title as Ezra while they were in Pensacola. During their time in Pensacola, they worked on the same docks and most likely in the same gang, a group of stevedores/longshoremen who worked on a ship. Charlie gave probably the largest push for Ezra to get a job at the port giving him an inside man to get a job. Charlie could speak with the foreman to get a direct line of employment for Ezra.

The pay may not have been much but it was enough. Ezra could make between 30 to 60 cents per hour in 1900. This to many does not sound like a lot of money. In 2018 this would equate to 9 to 18 dollars an hour. For Ezra calculating a yearly wage would have been difficult. He did not work a set amount of hours each week or a certain amount of days each year. He worked when the ships were in port. But with a rough estimation, it can be assumed that Ezra could make up to 37,000 dollars a year in today's dollar.

Port life gave Ezra the ability to see people from different parts of the world. Be them from the other parts of the United States or from different countries they may have stopped in that port. By meeting these people he may have wanted to travel himself.

Ezra was of a long line of African American men seeking life at the port and on the sea. He like many others used it as a way to fund his family and to escape the racial tensions growing in the south. Being a stevedore/longshoremen gave Ezra the ability later in life to travel up north and see more of the world. The maritime industry has been a long-standing employer of all men no matter the color. Ezra took the opportunity and sailed with it.

For further reading:

- Barnes, Charles. The Longshoremen. 1915. At Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.russellsage.org/sites/default/files/Barnes_The_Longshoremen_0.pdf

- Blanck, Maggie. “ Stevedores, Dock workers and Longshoremen.” Occupation of Maritime Workers. http://www.maggieblanck.com/Occupations/Longshoremen.html Accessed March 31, 2019.

- Cassedy, James. “African Americans and the American Labor Movement.” National Archives. December 7, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/summer/american-labor-movement.html.

- Flynt, Wayne. "Pensacola Labor Problems and Political Radicalism, 1908." The Florida Historical Quarterly 43, no. 4 (1965): 315-32. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/stable/30140132.

- Bowden, Jesse, Gordon Simons, and Sandra Johnson. Pensacola Florida’s First Place City. Norfolk, VA: The Donning Company, 1989.

- Shofner, Jerrell H. 1972. “The Pensacola Workingman’s Association: A Militant Negro Labor Union during Reconstruction.” Labor History13 (4): 555–59. doi:10.1080/00236567208584227.

- Trask, Sherwood. "Levee Songs." Poetry 30, no. 5 (1927): 249-51. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/stable/20576149.

- Woodrum, Robert H. “‘The Past Has Taught Us a Lesson’: The International Longshoremen’s Association and Black Workers in Mobile, 1903-1913.” Alabama Review 65, no. 2 (April 2012): 100–136. doi:10.1353/ala.2012.0025.

- "Waterside Characters. The Work Done by 'Longshoremen and Stevedores in New York Harbor." Leavenworth Advocate, (October 9, 1888): 1. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2:12B762C609CC7FC8@EANAAA-12BCB84174E42558@2410920-12BBC8F056B38218@0-12E4B0F914C08BB8@Waterside+Characters.+The+Work+Done+by+%27Longshoremen+and+Stevedores+in+New+York+Harbor.