Navigating into Pensacola is complicated. Strong currents, shifting barrier islands, shallow sand bars, and devastating storms affect the channel, making a safe landing in Escambia County an uncertain endeavor. Each excursion into the bay offers a unique experience, whether a ship visited five years ago or five months ago. Identifying historic navigational aids entailed not only recognizing sanctioned uses of travel markers, such as buoys and lighthouses, but also required going beyond the obvious to incorporate the larger landscape, as well as locating how those methods changed over time. The National Park Service defines Historic Aids to Navigation as lighthouses, buoys, channel markers, sound signals, daymarks, and lightships. In contrast, mariners define navigational aids as anything they can see from the deck of a ship that helps them get to where they want to go. Using this idea, the navigation landscape flourished as it went from only a few official markers to dozens of structures, points, geographic features, and landmarks. In total, the navigation aid inventory currently consists of ninety-three sites – and will grow in future projects.

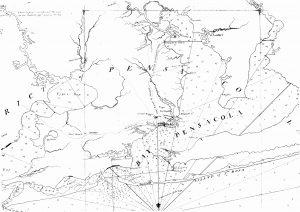

Early efforts to minimize risk for entering the bay were hand-drawn maps created by Spanish surveyors in 1700. By 1768, British surveyor George Gauld created a thorough map of the bay, marking everything from the ‘signal house’ on Santa Rosa Island to ‘Terry’s house’ near present day Warrington. After the United States seized control of the area, Pensacola experienced unprecedented levels of growth in both population and industry. Increasing industry meant more ships and more ships meant more industry. In 1800, the Federal Government created the United States Coast Pilots to assist mariners with entering ports. The 1822 Coast Pilot includes sailing directions that use major landmarks to indicate the entrance to Pensacola. Among these landmarks are Fort Pickens, the Pensacola Lighthouse, and the various railroad wharves that jut into the bay. As the city evolves, so do the methods of navigation. Despite the advent of Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) and digital mapping, visual navigation aids continue to guide mariners into port. Earth scientists use these historic aids to discover how the landscapes change. Archaeologists use these resources to identify potential sites for survey, such as old ship moorings. Utilizing the broader definition of navigation aids, a landscape emerged that benefits multiple disciplines and contributes to the greater understanding of the Pensacola community.

Featured Sites

Recommended Readings

Blunt, Edward M. The American Coast Pilot; Containing the Courses and Distances Between the Principal Harbours, Capes, and Headlands, on the Coast of North and South America. 10th edition. New York: Edmund M. Blunt for William Hooker, 1822. NOAA Office of Coast Survey.

Delgado, James P. and Kevin J. Foster. “National Register Bulletin No. 34: Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Historic Aids to Navigation.” U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

Office of Coast Survey. “Historical Map & Chart Collection.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://historicalcharts.noaa.gov.

Author: Jessie Cragg

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5133-8384